One of the goals of the job advertisement and job application process is to make it evident to potential applicants whether or not they are qualified. Ideally, only those who are qualified will apply for the job. But the reality is that in most Government of Canada application processes, there are a significant number of people who apply and are not deemed qualified, even at the initial screening phase of the process. Screening applicants who aren’t qualified contributes to the length of time managers spend on a staffing process.

In the context of designing this cascading hypothesis, the team was also aware of external research indicating that there are gender and diversity considerations when it comes to self-assessment. In particular, there is data suggesting that men are more likely than women to self-assess favourably when it comes to issues of job readiness. Any research design that Talent Cloud developed would need to factor in awareness of this risk, and ensure that equity-seeking groups weren’t unconsciously disadvantaged by the design.

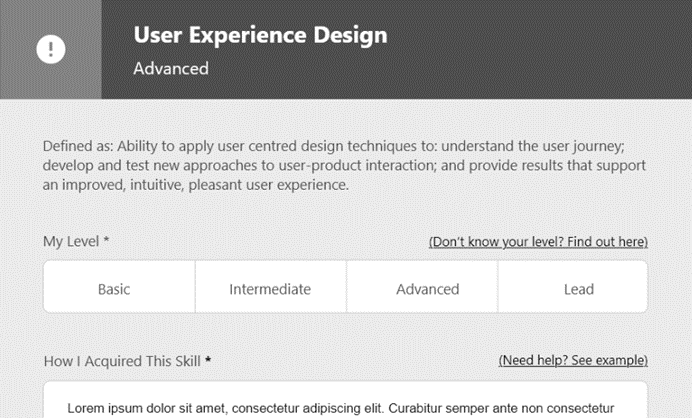

Talent Cloud decided to include an active step in the application process, where applicants had to self-assess and indicate their level of skill proficiency for each skill. Our thinking was that this active step would reduce the number of people who falsely claimed they had the required skill proficiency. However, we were worried that this could bias the pool of applicants by disproportionately affecting equity-seeking groups who might be more likely to self-assess below the required level.

For this reason, we decided to accept all applications regardless of the skill level the applicant indicated. It’s common practice in web forms to block the submission of applications until the user has indicated they meet all requirements. In this case, we made the deliberate decision not to force candidates to claim that they had the required levels just to submit their application.

This effectively created a new group of applicants that we separated out for managers before they started their review (as part of the sorting in the Applicant Tracking System developed by Talent Cloud on the Manager Portal). This new group could be skipped by managers when many applications were received, but could also be used to explore our hypothesis that some applicants would incorrectly self-assess, and should in fact be considered for the job. If managers regularly thought the candidates had under-rated their skills (and were in fact well qualified), then it would be plausible that this step was introducing undesirable outcomes, and we would need to investigate further.

Roughly 15% of all applicants (155 out of 1004) indicated that at least one of their skill levels were below the required level. Looking at the breakdown between hard and soft skills, only 16 of those 155 were for soft skills.

In all cases where managers reviewed these applicants (and Talent Cloud was able to follow up with them), the manager was in agreement that applicants didn’t meet the required skill level, and those applicants were not invited for further testing.

Several applicants interviewed who did indicate lower skills levels shared that they knew they did not meet the requirements, but wanted the manager to see their application anyway. This indicates that, at least in those cases, the applicants were not accidentally submitting erroneous data, and that the platform intervention was functioning as designed.That said, the addition of this requirement in the application process also created an additional step for applicants - one that caused some to delay submission of their applications due to uncertainty over the skill level they should self-select. Applicants reported that they were often unsure of their level, and this led to procrastination in submitting the application. (And of course, we can’t see who didn’t end up applying because of this feature.)

Given the constraints on the data Talent Cloud was permitted to collect on the platform, we weren’t able to cross-reference quantitative Employment Equity data with applications submitted claiming a lower level of skill proficiency than the job required. In order to correct for this absence of data, the team ran a deeper qualitative analysis of applicants for a small number of processes run on the platform. While the sample size was small and results are definitely inconclusive, there was no overt trend on the platform towards equity-seeking groups being more likely to self-assess at a lower level.

(Further study would be required to confirm this finding, and to look into whether or not the bias-reduction design in the skills model was a factor in ensuring that equity-seeking groups weren’t over-represented in self-assessing at a lower skill level. Our platform values and showcases different life paths for acquiring skills, and there could be a potential connection to the way in which equity-seeking groups self-assess in this new ecosystem, compared with more traditional application processes. See also Skills Instead of Experience in Section 3 of this report.)

On the surface, a 10-15% reduction in the applicants to screen would seem to be helpful to managers. But this is only part of the story. Of the remaining applicants, roughly half were eliminated by hiring managers at the initial screening, indicating that a majority of applicants were still overestimating their skill level. Because of time savings and other volume management components on the Talent Cloud platform, managers estimated that this 10-15% reduction in applications only saved 1-2 hours of time in the initial screening phase. Applicants, on the other hand, expressed that in some cases this element of the application process created uncertainty and anxiety about accuracy in self-reporting, and delayed the submission of applications.

While there may be many cases where self-assessment is a useful tool in advancing the applicant selection process, Talent Cloud didn’t find that it was as useful a component in the initial application phase as we had hoped it would be. This held true for both hard (occupational) and soft (behavioural) skills.

As a result, this component of the application design didn’t make it into the massive overhaul of the application process (called Timeline) the team released in 2021. (For more on the new model, take a look at Skills Instead of Experience in Research Section 3.) Instead, we’re moving more in the direction of helping improve the three-way conversation between managers, applicants and HR advisors around what “qualified” looks like for a given skill, and what information applicants need to provide to help managers make screening decisions that value diverse life paths for acquiring and demonstrating skills.