Our team cares deeply about building for accessibility. Accessibility is about making things that anyone can use. It’s about investing the time in making a product that works for everyone, and caring about how easy it is to use, regardless of a person’s individual needs when it comes to accessing content. Being a product team in government we are afforded the time to do it right, which some of our developers have lamented is not often the case in the private sector.

The world we want to be part of is a world where everyone’s skills and life paths are valued, so in this instance we’re glad to be building a product in government where we can focus efforts on doing the right thing.

In the context of an application that is always being changed and improved, it’s not good enough to be accessible at a single point in time. Even if it were, there are always ways to improve further. Instead, we’re now thinking about “being accessible” as a process of continuous improvement.

Every feature we build needs to be accessible, but like making a great plate of nachos, you need the right ingredients to even get started. For our team, a few things have stood out as being particularly helpful over time.

In-House Expertise: One of the first developers we hired onto the team specialized in building accessible web applications and this has proven to be immensely important for our product’s development. Having someone on the team that people can turn to for advice helps get everyone familiar with their responsibilities and sets expectations.

Accessible Design System: Giving developers the tools to help them is also key. Over time we’ve been able to build an in-house design system that does a lot of the accessibility work for our developers: ensuring color contrast is adequate, components like the menu or modals (pop-ups) behave properly, and key accessibility considerations are already built into the design options.

Building for Mobile Devices: Our design system, and application, are built to work on screens of all sizes, whether computer screens or phones. This is important for lots of users, but increasingly we feel this is an important part of building an accessible application. We can’t reliably make assumptions about the ways people use assistive technologies or the devices they need. People are diverse and we need to build accessible products for as many use cases as we can. In today’s world, that has to include mobile devices.

Automated Testing to Catch the Easy Stuff: Other tools for our developers like Google’s Lighthouse, which can automatically catch some accessibility concerns, have also become staples of our development process. These tools can give you a false sense of accomplishment though and rarely mean that your application is accessible on their own. For us, getting these automated tools to pass at 100% is the easy part, getting the application working acceptably in the real world is the challenge.

Testing with Real Users to Catch the Nuances: For actual testing of our application with assistive technologies, we’ve dabbled in using screen-readers ourselves, but haven’t stuck with it. While useful, the practice is flawed because we don’t use assistive technologies the way someone who needs them everyday. Even if we did, it’s still only one combination of assistive technologies and there are many more to consider. Instead of trying to do final accessibility testing ourselves, we now rely on a third party service that connects us with real people that use assistive technologies. The company we’ve used for this is called Fable and we have their users test our features before we consider anything to be ready for the public.

The best part is that these testers will be using a variety of different browsers and assistive technologies, so you can have more confidence that your application works for everyone. Working with Fable allows Talent Cloud to encounter and be tested against “edge cases” that wouldn’t be caught by automated testing, but are a critical part of building a truly inclusive product.

The Accessibility, Accommodation and Adaptive Computer Technology (AAACT) offers training, tools and testing services to help departments create accessible digital content that is inclusive by design such as documents, presentations and web content. For those in the Government of Canada looking to learn more about accessibility, this team is a great resource.

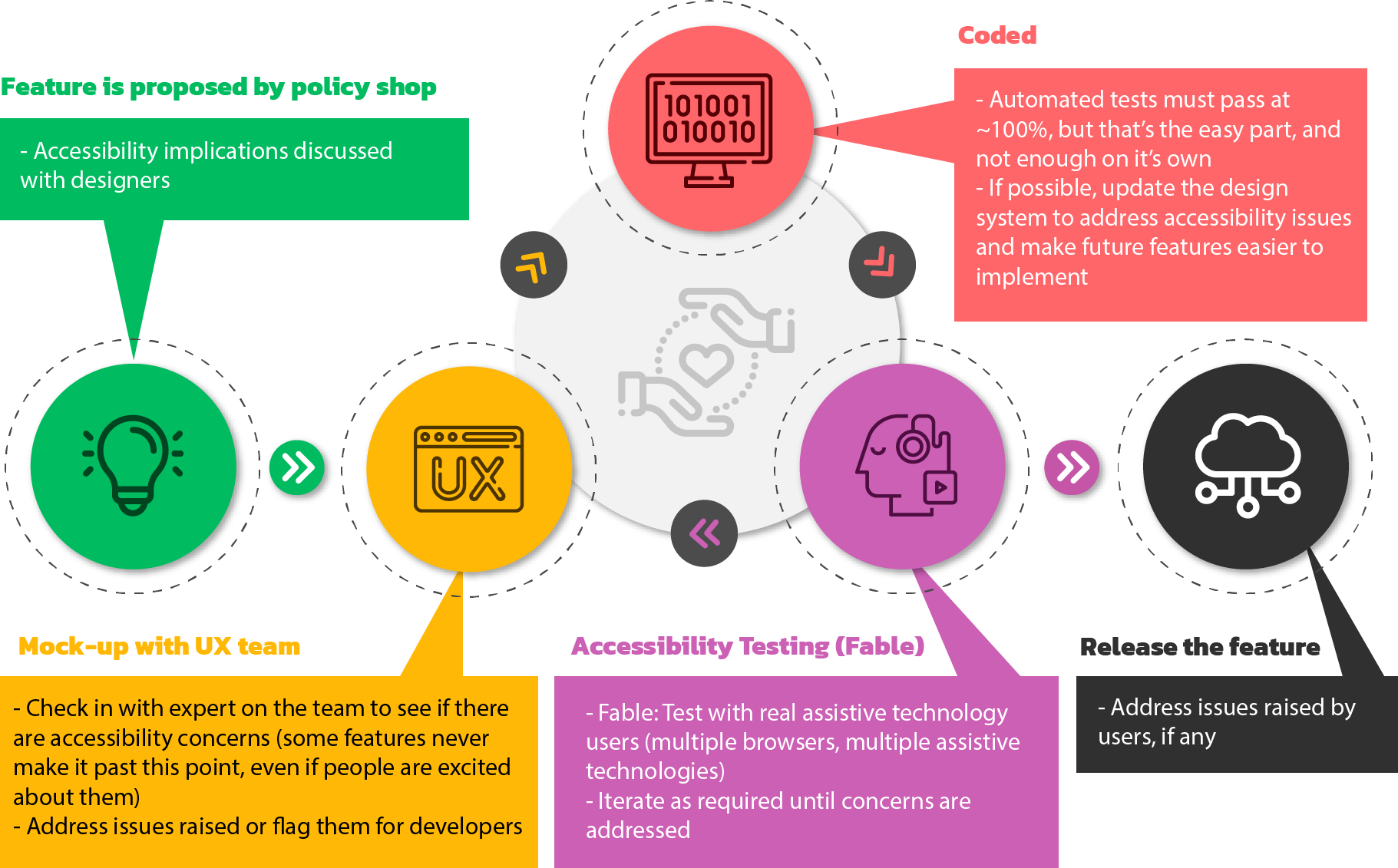

Testing for accessibility with real users is an important part of our process for building an accessible application, but it’s far from the end of it. Accessibility gets considered at almost every stage of the development process.

We wanted to share an example of how much working with real users changes the outcome of the product, even after a design passes a number of automated accessibility tests. This is meant to highlight that an algorithm alone shouldn’t be what gets to determine if something is considered “accessible.” This can only truly be determined by those with real world experiences of requiring accessible solutions.

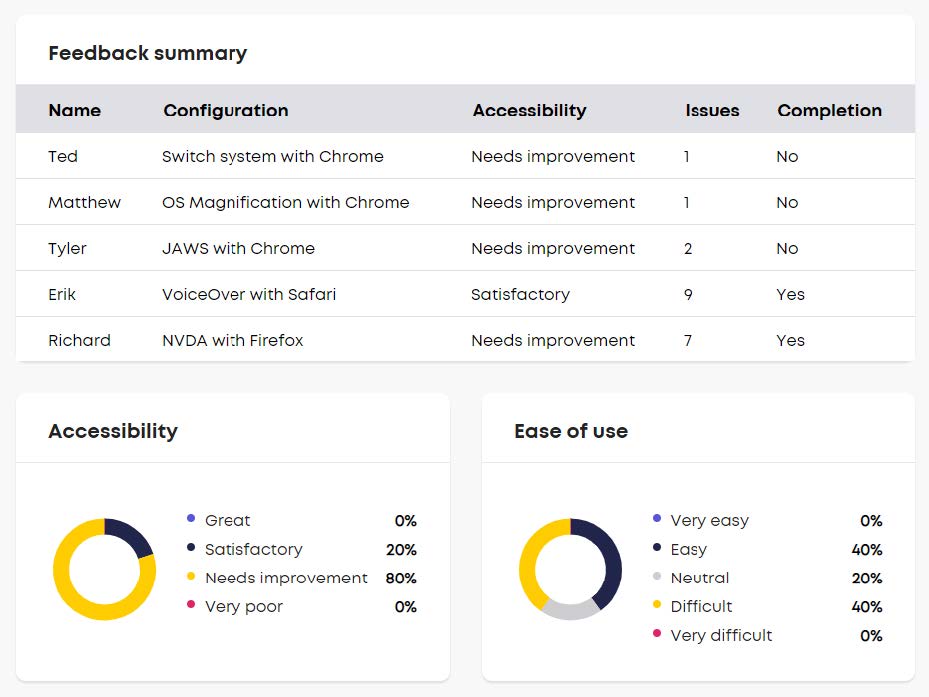

Here are two before-and-after reports from Fable that we received for the new reusable menu for our design system. Our first attempt followed standard practices and we made the assumption that tabbing through the menu would be the best way to navigate it with the keyboard. We had heard that menus could be some of the most difficult elements to navigate with assistive technologies, so we were expecting to have more work to do but the results were even worse than expected. The menu seemed to work fine to us, but users were simply unable to navigate it.

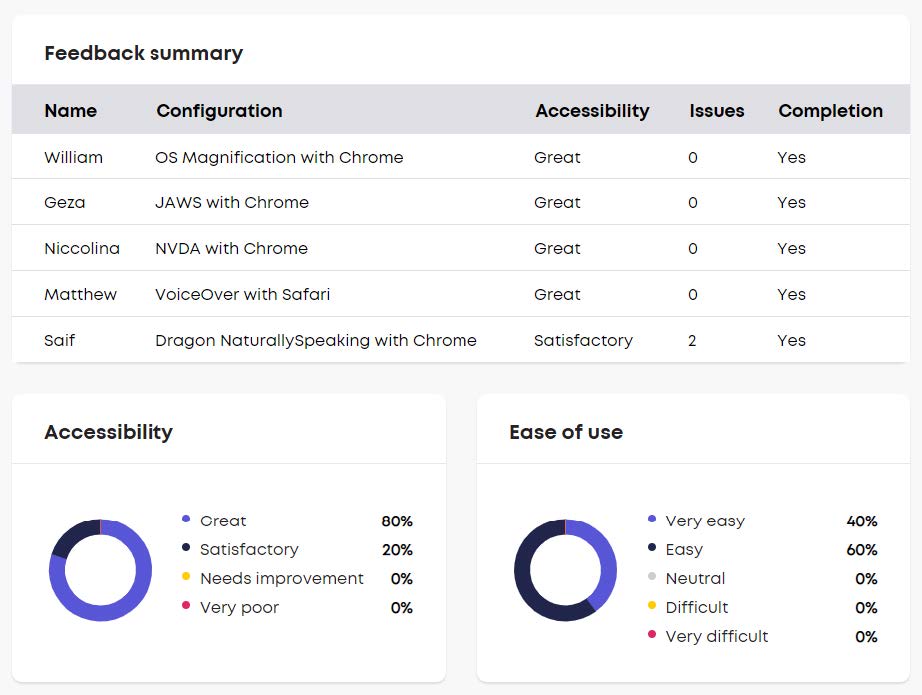

A lot of effort and research went into our second attempt. Descriptive text was added to explain how to navigate the menu, we switched to a combination of tabbing and arrow keys for navigation, and the escape key was added to close submenus to give just a few examples. The results of our second round of testing were completely different. People with a variety of combinations of assistive technology and browsers were now able to complete the same tasks from before. Menus can be difficult to get right, so this felt like a big win for our team.

Our approach to building accessible applications has evolved a lot since we first started. Because we’re always improving our application, it means we are continuously working to improve the accessibility of our site too. The lessons that have been learned over the years about product design and development are equally applicable to building for accessibility. The best way to obtain the outcomes we want, whether it’s cyber security, interactivity or accessibility, is to build them into each part of the process and test with real users. This has proven time and again, to be more effective than tagging on a compliance exercise at the end of the process.