High application volumes are a challenge for managers, especially if many of the applications turn out to be a poor fit for the position. But how many applications should managers be hoping for in order to yield a strong hiring result? And is it even possible to influence the behaviour patterns of applicants in order to optimize the volume of applications?

Talent Cloud ran a series of workshops in 2017 to better understand the steps and choices applicants were making in the staffing process. As part of that process, managers identified that their preferred number of applications to receive was 20-30 at the initial screening, and 5-10 for interview, but that the number of applications received was often several hundred. Managers reported that they found this volume overwhelming, leading to procrastination and cancelled processes.

One of the most illuminating findings from that user engagement was the identification of a specific behaviour that was, at an aggregate level, contributing to high application volume and low quality fit. HR advisors were aware of the behaviour as a factor in longer times to staff, and hiring managers associated it with poorer hiring outcomes.

The behaviour pattern we identified was referred to by applicants as the “brute force attack” application practice - a term workshop participants shared, not one we came up with ourselves. In our research, applicants reported using the “brute force attack” application practice as a common strategy. Basically, they applied for anything and everything where they thought they might even remotely meet the selection criteria.

Most applicants reported that they didn’t clearly understand why they got accepted into pools or jobs for some processes, but failed others they thought they were more qualified for… and applicants reported that they had low success rates overall in applying. As a result, applicants reported developing a “try everything” approach. Most in the workshops reported applying for at least 10 jobs in the last 6 months, with a similar pattern of feeling like they were only a strong fit for a couple of them. Some even reported applying for 30-50 jobs in the past year, and estimated that they were a good fit for only 5-10 of those jobs. This apply-despite-not-believing-I’m-qualified behaviour was consistent for both external applicants and internal GC employees looking for promotional opportunities. A sense of confusion about “what gets you in” was pervasive.

So why continue the practice, even with a low chance of success? Why apply, even in cases where applicants reported not wanting the actual job? Applicants told us it’s “common knowledge” - or at least common belief - that once a person gets into government, they can move around easily, and seek a better fit job from the inside. (An internal mobility rate of ~12% in 2019-20 in the Government of Canada, and a promotion rate of ~13 %, would seem to corroborate the idea that once inside government, many people move to a different position that appeals more to them.)

For some hiring processes, high volume is the targeted outcome, such as when the Government of Canada gathers large pools of talent through recruitment drives that are open for several months. Numerous hiring managers from various departments pull from these pools, applying generic work descriptions. As a result, there’s little rationale to take behavioural steps to reduce application volume and optimize applicant fit.

But for individual hiring managers running a process for their own team with limited time and energy reserves, high application volumes are a challenge.

While it’s easy to understand the rationale that creates the brute force application behaviour, if it occurs at a large scale this pattern can lead to a massive number of misaligned, long shot applications that bog down the entire hiring system, placing a time and energy burden on HR advisors and managers, who are already stretched thin.

There are also diversity and inclusion factors to consider. There is external behavioural research showing that men are more likely than other groups to claim that they are ready for advancement or qualified for jobs. As a group, men reported often applying to jobs when they felt they were 60% qualified, compared with women, who reported waiting until they felt they were 100% qualified before applying. If this external research holds true for applicants to Government of Canada jobs, this could have significant GBA+ implications for application rates and hiring outcomes. It’s something that we wanted to be aware of when intervening to deter applicants who weren’t fully qualified.

If managers say they prefer to see 20-30 applications, we should aim for this volume and test to see if it’s actually the number that produces the best hiring outcome. This would require several interventions to address the high volume of applicants typically seen in government HR processes.

Talent Cloud reasoned that if the brute force attack application approach was causing high-volume, poor-fit application practices, disincentivizing this behaviour might improve time to staff and help increase the average quality-of-fit in the applicant pool.

Talent Cloud hypothesized that the following interventions would help address the brute force attack approach by applicants and would lead to fewer, but higher average quality of applicants.

While we needed to convince applicants that there was nothing to be gained from the brute force behaviour pattern when applying for jobs on our platform, we needed to do so in a way that was psychologically safe, not undermining. This was especially important in the context of encouraging diversity and inclusion on the platform. When designing, we needed to maintain a conscious awareness about not inadvertently deterring members of underrepresented, equity-seeking communities who might be more likely to self-select out, even when equivalently or more qualified than others.

Confirming whether or not our four interventions to deter this brute force behaviour actually worked is challenging. This is because of other interventions on the platform that were simultaneously encouraging more applications from a diverse range of applicants, many of whom had not applied before to government jobs. (Basically, we wanted to increase applications from diverse, high-performing talent, and reduce low-fit applications.)

So we don’t have a conclusive statistical test that allows us to confirm if these are the right solutions to this specific problem.

It’s important to note we couldn’t survey those who decided not to apply based on the nudges we made to change their behaviour pattern. Those who opted out simply never showed up as a data point for us. So instead, we started looking for what was not there: namely, were applicants in Talent Cloud processes applying for everything they could or were they more targeted?

In terms of applicant volume, we were able to track application rates, and monitor these as we introduced new features on the platform or changed our advice to managers (e.g. when we began limiting the volume of selection criteria to a more optimal range, we saw the volume of applications move into the target range.)

We conducted careful analysis of hiring outcomes in comparison to the volume of initial applications and the rate at which applicants were screened out during each successive assessment phase. We also looked at outcomes when managers were left with too few top applicants, and other factors (such as long completion times for security screening and HR finalization) that led to the top hire choosing another position, and leaving the manager without a hire. We also cross-referenced this quantitative data with qualitative interviews, to understand exactly how well managers were doing with the target range of applicants they told us they wanted (20-30) and whether or not it mattered if a manager was seasoned or new to hiring.

“Behaviour patterns matter in reducing time to staff.”

Talent Cloud was able to provide a platform that encouraged managers to optimize their job advertisements and assessment plans to produce a smaller volume of applications, resulting in fast processes with strong hiring outcomes.

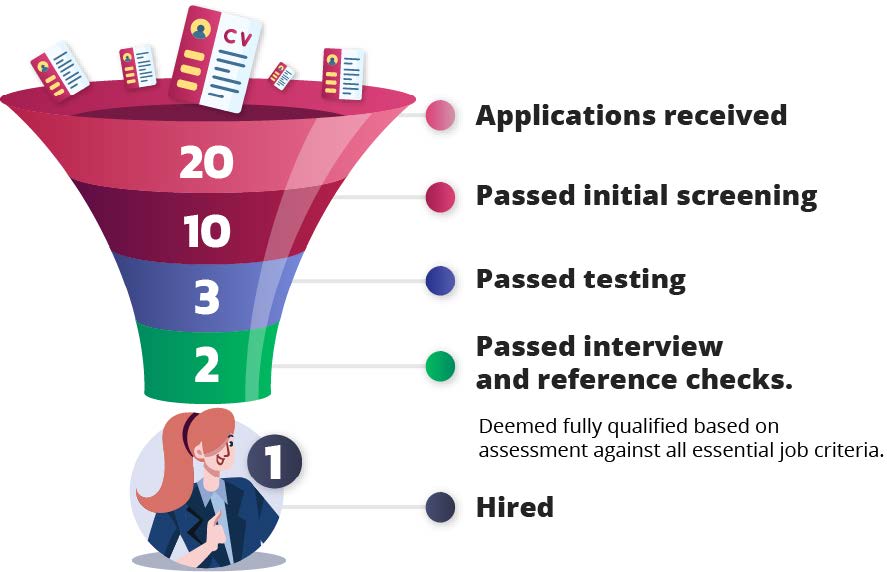

Talent Cloud job advertisements drew an average of 21 applications. Of those, nearly half (44%) passed the initial screening, 14% passed testing, and 9% passed the interview, indicating they had all the skills required for the position and were qualified to receive an offer, pending language testing and security.

The proportion of candidates that make it through each phase of the hiring process, also known as the hiring funnel, is an important metric that looks at both the final outcome (did managers get a hire?) as well as the performance of the applicant pool at each step (the drop off rate at each successive assessment phase).

Talent Cloud was able to impact the behavioural choices of the manager to help them design a job advertisement that would attract the targeted number of applications. By the end of the experiment, the team was able to predict with reasonable accuracy how many applications would be received by a manager based on the components of the job advertisement, and could work with the manager to amend the job advertisement to increase the chances of getting a hire into the target range.

The Talent Cloud hiring funnel is based on hiring processes that went to completion. That means that we include processes that didn’t go well, for example job advertisements that didn’t draw any qualified candidates. As long as the process isn’t still in progress in 2021, or was cancelled by the manager/department before it was completed, we included it in these results.

This diagram simplifies these findings, roughing it out into rounder numbers for managers and HR advisors to use as target values.

Although managers told us initially that they thought the optimal volume of applicants was 20-30 in the initial applicant pool, this proved to be too low a number for optimal results. Most Talent Cloud hiring processes successfully fell into this 20-30 range of applications, but based on data gathered, we’re recommending that a slightly higher volume of applications (30-60) is actually better. Our analysis led us to believe that this initial target of 20-30 applications reflected how many applicants managers felt they had the energy to deal with, rather than the optimal number for producing the best hiring outcome. That said, manager energy and enthusiasm levels have to be taken into account in a staffing process, otherwise it leads to long delays and cancelled processes.

There was a definite connection in our experiment between volume of applications, manager behaviour patterns, and hiring outcome. We found that the optimal target range of applicants for a new hiring manager was 30-40. For seasoned managers, who had a larger frame of reference for screening applicants, the optimal range increased to 40-60. Based on the hiring funnel data, this would leave new managers (who followed other Talent Cloud steps as designed) with ~6-8 fully qualified applicants, and seasoned managers with ~8-12 fully qualified applicants. An applicant pool of only ~20 applicants ran the risk of failing to produce a hire, particularly if the hiring manager delayed, even a little, at any stage of the screening and assessment process.

Seasoned managers, on average, processed their applicant pool more quickly than new managers and were more likely to do it themselves. They were also often in a position to make multiple hires (either onto their team or by matchmaking in their organizations). On the other hand, receiving more than 35 applications for a new manager created delays - either through procrastination behaviours or because they sought additional help from HR services. This added several weeks to the hiring process (months, if the HR services were a procurement arrangement). These delays, in turn, cost new managers their top applicants, and led to several failed processes in our study. This is why, for newer managers, fewer applications and fewer fully qualified applicants can actually increase the chances of a successful hire. There is a balance to be struck between application volume and processing speed, which can impact the final outcome. (See also Impact of Speed on Retention of Top Talent in Research Section 4.)

The research led to the discovery of an optimal target range for applications, but what about the other side? What about impacting behaviours so that applications arrived in a volume that optimized the hiring outcome?

Talent Cloud had success in relation to the efforts to reduce the number of under-qualified applications. While it’s difficult to claim conclusively that these interventions worked, the “qualified to receive offer” rate for Talent Cloud is 9%, meaning roughly 1 in 11 people applying were assessed as having all the essential skills required for the job. The industry average is much lower, sitting ~2% or 1 out of every 50 applicants is fully qualified (Jobvite, Harvard Business Review, Knowledge@Wharton, Glassdoor).

In terms of multiple applications, out of the 1000+ individual users submitting applications through the Talent Cloud platform, which hosted 50+ positions, only a single person applied for more than 10 jobs. In essence, the brute force attack behaviour only accounted for 0.09% of total applicants. Talent Cloud did observe multiple applications in smaller volumes (approximately 7% of applicants submitted between 2 and 6 applications), but this occurred where we hoped to see applicants using their reusable profiles to apply to multiple jobs at similar levels and classifications. No applicants submitted 7-11 applications, indicating a break in the behaviour pattern between those who applied to multiple similar positions, and those applying for many distinct positions. In summary, Talent Cloud noted a clear absence of the brute force application behaviour on our site.

The steps we designed and implemented on our platform to optimize application volume and specifically to deter the “brute force application” could be applied more broadly. In order for the Government of Canada to see these benefits at scale, changes would need to be made to the platform managers were using to hire, in order to ensure system-wide change management.

We believe the interventions listed above, as well as the five factor matching approach (optimizing talent-to-team fit), were significant factors in changing applicant behaviours and tailoring the volume of applications to the target range we aimed to produce. This wouldn’t be available as a deterrent in cases where departments are running larger pools with generic information. However, when running a pool, a larger volume of applications may not be a concern, and potentially the need for a rapid process is also less significant, reducing the rationale to apply these interventions.

But for managers looking to staff quickly for roles on a specific team, we strongly recommend deterrents in the language on the job advertisement that will dissuade those who are applying for any reason other than actually wanting to be selected for that specific job. We also recommend optimizing the process (to the extent possible on the platform being used) to target a range of applications optimized for the manager’s level of experience in hiring. This is one case where more is definitely not better - top talent will only wait so long, and speed is of the essence.